The Mattering Map

How alike we are in all our differences.

Somehow or other, I’ve ended up living a life where I’m occasionally interviewed. I never get used to it—the sense of its absurdity.

And now there’s this. My own Substack. Or perhaps my own Substack. This is only a test. We’ll see how it goes. I’ve been assured by friends who write for Substack—Elissa Straus (Made with Care), Ruth Whippman (I Blame Society), Barry Lam (Hi-Phi Nation)—that nothing is irreversible here. You need not commit, and I need not commit.

Still, it’s no mean feat for me, taking yet another step into the public space that still holds terrors for me.

As a child, and well into college, I was so shy that my greatest hope, as well as my greatest fear, was that people would fail to notice that I exist. The act of speaking, even within my immediate family, required far more courage than I could muster. I stopped speaking my mind for so long that it seemed to me that I had lost it.

And now, only three short paragraphs in, you know more about me than my therapist does—or would if I had a therapist.

Sometimes an interviewer—of course knowing nothing of the kind of young person that I had been—will ask me whether there’s something I wish I could tell my younger self, something helpful or encouraging. Yes, I say. I’d tell her that she was going to end up living a life in which someday she’d be asked by an interviewer if there’s anything she’d like to tell her younger self.

A good answer, I think. One that says it all without giving anything away. And making hay of propositional self-referentiality, which is always an added bonus.[1]

Once I was being interviewed on the podcast Philosophy Talk, which was then hosted by the two Stanford philosophers John Perry and Ken Taylor. (Ken has sadly since died.)

I mentioned to John Perry on air that, during the brief time that I’d attended UCLA, I had taken one of his classes. He was shocked, since he had no memory of me at all. I even quoted him back a funny thing he had said in class just to prove to him that I’d really been there. It was about Kant—or rather philosophers who study Kant: that the reason they all end up claiming he was the greatest of all philosophers is that otherwise they’d have to admit they’d wasted years of their lives trying to decipher what the hell he was endlessly going on about. Yup, said Ken to John. That sounds like something you’d say.

During the break I heard John still expressing his dismay to Ken that he couldn’t for the life of him remember me, especially since the class I’d attended had been fewer than 15 students. I wanted to reassure John that there was nothing wrong with his memory but rather it was just as I’d always hoped and always feared back then—that my existence wouldn’t cause a ripple in public space.

While we’re on the subject, here’s another funny thing John Perry said in class, this time about the philosopher Bishop George Berkeley. Berkeley didn’t believe in the existence of material objects. He argued that the whole idea of things existing independent of being perceived was incoherent. Esse est percipi, opined Bishop Berkeley. To be is to be perceived. So here’s the joke. Berkeley had promoted tar-water as a cure for many ills, including constipation.[2] John suggested that Berkeley might have had his own personal reasons for wanting to expel matter from the universe.

You see, John, I really had been in that class.

I don’t know why I developed my selective mutism. Like so much else that’s true of us, it was some incalculable mixture of nature and nurture. Whatever the cause, I hated my shyness more than anything else about me, and I found a great deal to hate about myself. I had my own self-damning way of twisting the Latin dictum of the possibly constipated philosopher. If to be is to be perceived, then I was not. Or at least I was the bare minimum.

The selective mutism is long since gone—so gone, apparently, that even the shame of it has dissipated enough for me to now own up to it.

The wonderful psychologist Donald Winnicott wrote that “Artists are people driven by the tension between the desire to communicate and the desire to hide.” For the first part of my life the latter desire had its way with me. But gradually the desire to communicate was able to find its way back to a voice.

So here I am, starting a Substack. Or perhaps starting a Substack. We’ll see. I’m easily discouraged when it comes to spouting my POV.

But at least now I can proudly lay claim to a POV—and on so many topics!

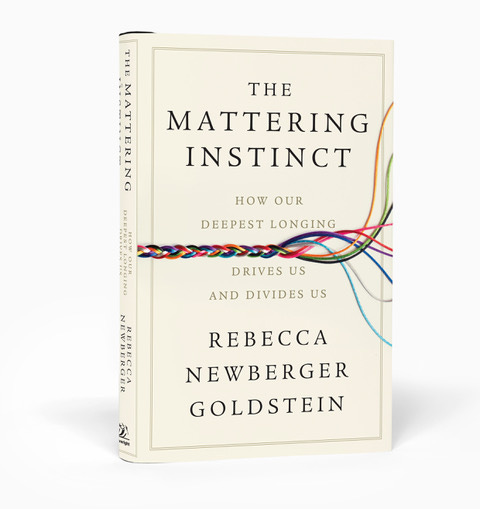

Here are a few that I’m thinking I’d like to explore with you here. First, there’s what I call the mattering instinct. I have a book coming out in January by that name.

As the sub-title suggests, this book is ambitious. It could easily have been 700 pages but it’s only 304. So obviously I left out a lot, which I’m eager to talk over with you.

I want to talk about mattering and politics, and mattering and religion, and mattering and death, and mattering and child-rearing, and mattering and anguish, and mattering and justice, and mattering and flourishing, and mattering and AI, and mattering and tribalism, and mattering and the meaning of life, and mattering and MAGA, and mattering and you and me.

It’s my 11th book, which isn’t bad for a person who has to do battle with the desire to hide away.

Of course, a lot of those former books were novels, which is a wonderful medium for someone torn between the two desires that Winnicott identifies. Writing my first novel while I was a yet untenured professor of philosophy, the ink on my PhD barely dry, I managed to do two big things at once: sabotage my academic career as an analytic philosopher and begin my journey of finding my way back to my own mind.

That novel was called The Mind-Body Problem, and it was in its pages that I first introduced the concept of the mattering map.

Yes, that’s how long I’ve been gestating these ideas about mattering that have finally come to fruition in the book I’m soon to publish.

Here’s how I introduced the mattering map back then: “A person’s location on the mattering map is determined by what matters to him, matters overwhelmingly, the kind of mattering that produces his perceptions of people, of himself and others: of who are the nobodies and who the somebodies, who the deprived and who the gifted, who the better-never-to-have-been-born and who the heroes. . . .Those who share my heroes are, in the deepest sense, of my own kind.”

As a philosopher, I would never have come up with such an idea—far too vague for the likes of me when I’m thinking analytically. It took me hiding behind my flagrantly non-analytic fictional character to come up with the mattering map as an explanatory concept.

That’s another topic I want to discuss with you, the relationship between philosophy and fiction writing.

To be continued. Or maybe not. This is only a test.

[1] Propositional self-referentiality refers to propositions that make reference to themselves. Propositional self-referentiality sometimes entails paradox. Here is an example: “This proposition is false.” Is this self-referential proposition true or false? If it’s true, then it’s false. But if it’s false then it’s true. The conclusion seems to be that it’s both true and false—a paradox.

[2] He really did. See George Berkeley (1747) Siris: a chain of philosophical reflexions and inquiries concerning the virtues of tar water (London re-printed: W. Innys: https://archive.org/details/sirischainofphil00berkiala/page/n7/mode/2up. Ironically, Siris was Berkeley’s best-selling publication while he lived. And despite John’s joke, which still cracks me up, Berkeley’s devotion to tar-water speaks well of him. Poverty and disease were rampant in the diocese of Cloyne where Berkeley was bishop, especially after the Great Frost of 1739-40.

Welcome to the scrum, Rebecca. I’m glad you overcame your shyness. I just got galleys of your book, can’t wait to read it. John

Oh - please keep writing here - I’m wondering how I haven’t come across your work before, and so glad to come across it now, and the range of it. (I’m a former humanities prof/Plato scholar and now doing/writing quite different things.)